Here is A Donor Presented by A Saint, attributed to the Flemish painter Dieric Bouts, a painting I have been using as a focal point to play with different material relationships between artworks and texts, to see what this can and cannot tell us about the people who produce them. As an artist and performer my primary interest is in people, and this puts me at the exact point of tension where it is unclear where a person begins and an object ends.

I first noticed the painting because of the hovering hand. Why is it there? Who does it belong to? I read the painting’s information card and learned that it was cropped from a larger alter-piece, dismantled during the Calvinist Reformation in Belgium. Typical of church paintings at the time the tableau would have been an allegorical lesson from the Bible. The faces of the characters would have been painted by monks in the church’s employ, using faces from members of the community for reference - it was not uncommon to see, for example, the face of the local baker masquerading as one of the three wise-men visiting the baby Jesus. The more money a patron donated to the church, the more likely their face would be used to depict a more desirable character, like St. Peter guarding the gates to heaven.

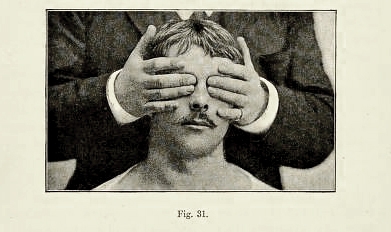

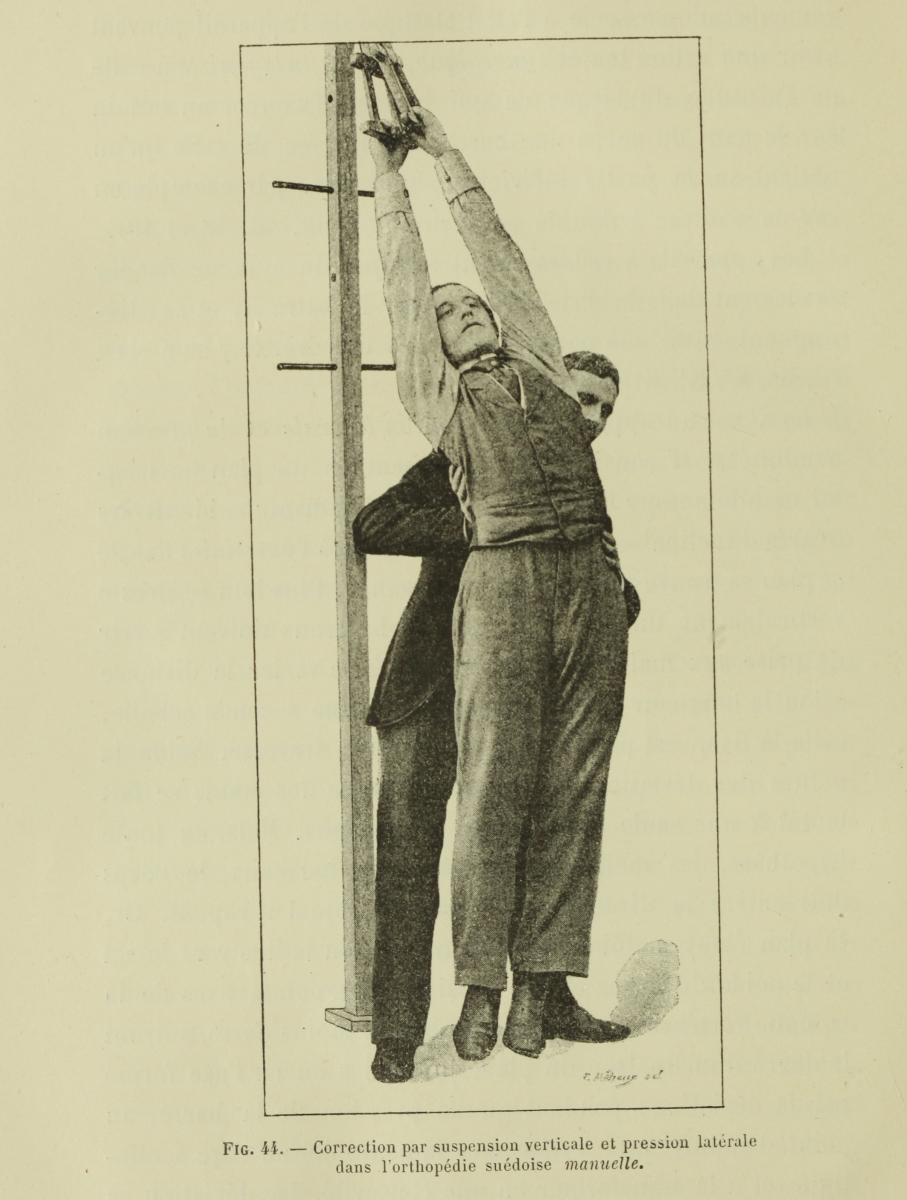

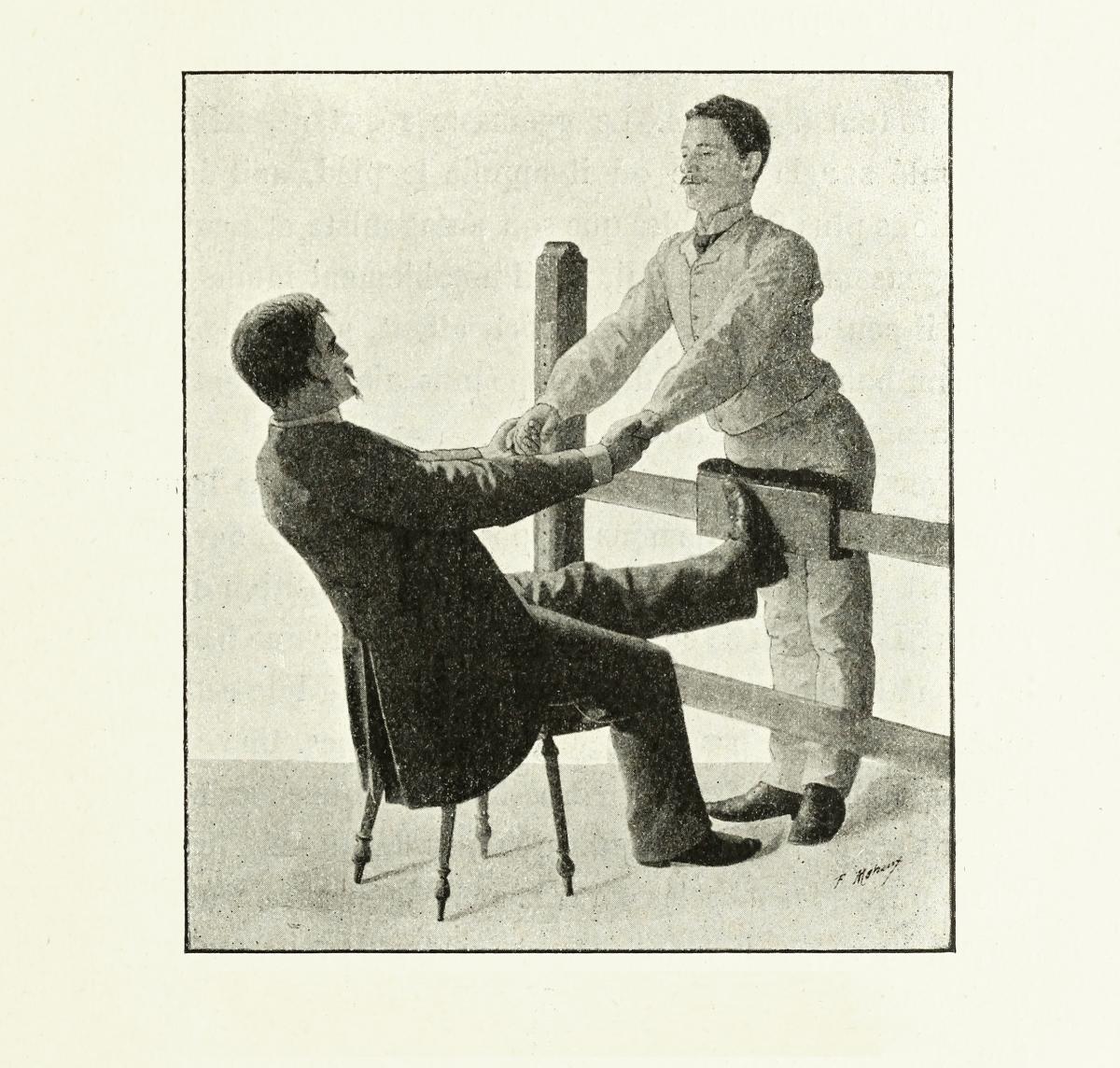

How does it feel to have someone’s hand resting on your shoulder in that way? How would it feel to see your face painted on the church wall in such intimate proximity to your landlord? Before I read to you I want to try an experiment. Please form a pair with the person sitting in front or behind you. The person in the back should put their hand on the shoulder of the person sitting in front. Please rest your hand on their shoulder and leave it there while I play you a song.

Earlier this year I delivered a text about this painting at a conference about myth at the University of Jendouba in Tunisia. Without reading carefully, I mistakenly believed that the hand belonged to the donor described in the title, who had then been turned into a curtain, and that the person seated was some other character from the locale. Drawing rather dramatic conclusions from this false premise I used the text to explore how the role of the artist existed as a profession at the time of the painting; how religious ideas about authorship and the scope of artistic activity as a profession dictated what images were created and how they were distributed. I use this strategy regularly in my practice, attempting to trace religious residue and unconscious attitudes in our conceptions of what art is and in what ways this dictates how groups of people relate to culture more generally.

If anything my blunder highlights a tension for artists who write; it is difficult to strike the right balance, or find harmony between the need for quality research and the freedom and level of disregard required to foolishly blunder ahead into unknown territory (in this case, the unknown territory of the past).

So now I will read to you the fruits of imagination, when not held in check by the firm hand of reason and careful (rather, ‘careful enough’) research.

[second reader]

…unlike Simon I am a good, honest butcher, taking pride in my trade, not assuming airs or venturing out to make a fortune on the purse of an aristocrat or the hopes of a foolish investor - I am a respected member of one of the few remaining guilds, and I wear my livery proudly.

So now Simon is enjoying the fruits of his gamble in a truly unChristian manner, wasting his profit by commissioning a portrait, as if he were some aristocrat. Imagine, thinking that hanging a picture of your face above the wooden kitchen table could trick anyone into thinking your house was comparable to the prince’s.

Mary was impressed by it, she said, that it wasn’t so bad, done by a poor Flemish fellow who was trying to follow his friend Dieric Bouts to Paris - Bouts had met with quite a large success in France and had written to say there were many Flemish painters finding patrons and exhibiting in the Salons.

The painter of Simon’s portrait, however, didn’t make it that far, moving from Haarlem to Ipswitch, trying to get by painting signs for shops and prows of ships. He used to paint religious panels in churches and gild statues. His dream was to move in the same circles as his friend Dieric, to train in an academy. He said that once he had the training he’d be able to sign his name to his paintings. When he painted instructive allegories in the church he would sometimes, and of course I only mention his error so that we might be instructed not to sin in this way ourselves, chasing after vainglory when all worship should go to God in heaven, he would sometimes paint his face onto the figure of St. Francis, or St. John looking to heaven as the holy spirit descended in the shape of a dove, or on the body of a bearded wise-man traveling to visit the holy family. Apparently most of the painters work this way, I suppose it’s one of those things, if God is in all things and is reflected in the form of man, why not use the face of your fellow painter to portray God’s likeness? I suppose the light of God is what shines through a painted face, the more accurate and reflective of human likeness the more clearly we are able to see God.

Brothers and Sisters in Christ would use each other’s likeness as a reference for the images they created, but what’s a painter to do if he’s by himself? Now that the monasteries are being sacked the monks who worked on panels or plaster murals now work by themselves on canvas. The monks illuminating manuscripts, the ones who weren’t beheaded anyway, have gone on to paint china and temper silver for royalty.

The panel paintings that weren’t boarded up and hidden behind plain, white plaster walls have been taken down and cut into pieces - I’ve been thinking of purchasing one actually - I wouldn’t be so vain as to have my own likeness painted as God only knows how far I am from his image, but I would display the portrait of a Godly man who used his wealth to bring about good works - this is the kind of man I try to be, and would encourage others to be.

Mary says she thinks we’re better off for having these painters coming into town, poor lot, they certainly can’t go back to where they came from for fear of being strung up, although with things the way they are here it might not be long before the fighting starts again. After Simon’s portrait was finished he offered to pay the painter to clean the chimney, as a favour, because he knew the painter needed the money.

At Simon’s dinner there was a fellow from one of the new reformers liveries, a manufacturer of linens and an educator. He was filled with a slow burning fire, convinced neither the church nor the state could ever do a good enough job turning people’s hearts and thoughts to the Word. He used his company to start educating young men to read, that they might be more easily led to theology. The signature on the painting we were discussing fueled in him a quiet rage - when I asked why it angered him he begged permission to share with Simon’s guests the story of another painter from the Netherlands, Bertel Thorvaldsen, a protestant who aspired to train with the masters in Rome.

Thorvaldsen won money to travel there and study classical sculpture, at which he was quite adept. He made a name for himself and built up a large studio, eventually gaining a commission to make a sculpture of the Pope Pius VII. This was no small compliment to his skill as it was the first commission granted to a sculptor who was neither Italian nor Catholic.

After some time he completed the work, and when he presented it to the Vatican a council announced the decision that his signature must be removed from the sculpture. No protestant would be allowed to sign a papal sculpture that sits in the great hall with the statues of previous popes, made by the hands of Catholic Italians. Thorvaldsen was not a man to be bothered by prejudice, but obviously had been influenced by his time spent in such a pernicious place. He told them not to worry, that he would make the necessary changes and return with the finished statue quickly.

A great deal of time lapsed, and Pope Pius passed away. The council eventually returned to Thorvaldsen and asked him about the statue, if it had been finished as promised. Thorvaldsen agreed to unveil the statue the following week. A week passed, and at the ceremony it became clear the signature had indeed been removed, but what should have been the face of Pope Pius VII had changed instead to be the likeness of Thorvaldsen’s own. There was nothing that could be done as the Pope was deceased, and so, what started out as the usual practice of an artist using his own face or the face of a close friend for reference became a perverse victory - for our reformer, this victory was far too Catholic in spirit and reeked of the kind of decadence he had dedicated his life to stamping out…

[end of second reader]

I first delivered my text at the University of Humanities in Jendouba, Tunisia, with my voice amplified by a microphone in a room of 200 people, 150 of whom had their heads covered. This should also give you an idea of the gender distribution. I lectured in English, while the majority of the students spoke French as a primary academic language.

Imagine me speaking to you in my loud amplified voice, full of assumptions about your understanding of how images work and how images relate to bodies and how bodies relate to texts, full of assumptions about how images, bodies and texts are separate and how it is my job as the artist who writes to heal this separation. The image projected on the wall behind me would have been far more appropriate if I had used this one.

So all of these separate things I’m sharing with you are an attempt to treat the relationship of text to artwork by analogy, as that of body to apparatus - the text, or script being a social technology that arranges bodies and voices within an apparatus -

and that of the writer to the artwork not as healer to patient (Boris Groys wrote an article in German where he says he believes that art is sick and it’s the critic’s job to heal it - I cannot gauge what level of irony he is employing), but rather, I’d prefer to emphasize the role of foolish co-collaborator,

and I’d like to put forth that any development of criticism is fairly meaningless without a community of participants who share a frame of reference. And it goes without saying that the shape of the frame will be determined by whatever social injustice and inequality is operating in that community, not to mention the dominant religion. The role of the court jester comes to mind.

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing describes in devastating detail exactly how the divisions of class and gender destroy in a person their creativity and capacity to create.

“’Sometimes when I, Anna, look back, I want to laugh out loud. It is the appalled, envious laughter of knowledge at innocence. I would be incapable now of such trust. I, Anna, would never begin an affair with Paul. Or rather, I would begin an affair, just that, knowing exactly what would happen; I would begin a deliberately barren, limited relationship.’ What Ella lost during those five years was the power to create through naivety.”

If I am speaking about this practice as one of working with material components, I must regularly remind myself of the importance to leave room for the components to be what they are; I would not want my writing or criticism to be the secular equivalent to ‘laying on hands’. I am chasing the impossibility of not letting my assumptions get in the way, of leaving room for myself to act from the place of the fool. This does not mean refusing to look at the existing political and social apparatus - if anything it means extra rigor in that regard, allowing for the discovery of gaps where that kind of naivety can operate and cause disruption.

The best part of the text I read in Tunisia was the question at the end - I had delivered it standing in front of a curtain, while my friend Miranda hid behind and rested her hand on my shoulder. The painting was projected on the adjacent wall for good measure; not only was the premise of the text false, I resorted to a rhetorical sledgehammer, being in an unfamiliar environment and feeling insecure if I had successfully collapsed the separation between image, body and text to an audience who had a radically different frame of reference. A student stood up and asked me, “Why did your friend stand behind the curtain and put her hand on your shoulder? Were you afraid of reading to us? Or did you just want company?”

--

Transcription of a performance lecture delivered on November 15th 2014, at Gallerie Box in Gothenburg, Sweden. Part of the art writing symposium “Nearly and nervous nearly and now” organized by Julia Calver and Esmerelda Valencia Lindström

The text referred to in the presentation, A Donor Presented by A Saint by Dieric Bouts, was first published online by TAG Journal [http://tagjournal.com]