“But how then is ambiguity manifested? What happens, for example, when one lives an event as an image?

To live an event as an image is not to remain uninvolved, to regard the event disinterestedly in the way that the esthetic version of the image and the serene ideal of classical art propose. But neither is to take part freely and decisively. It is to be taken: to pass from the region of the real where we hold ourselves at a distance from things the better to order and use them into that other region where the distance holds us – the distance which then is the lifeless deep, an unimaginable, inappreciable remoteness which has become something like the sovereign power behind all things”

Maurice Blanchot, The space of Literature.

The following is a brief summary of reflections that I felt the need to consolidate after attending a lecture by Anton Vidokle entitled “Art without work” which was delivered at the Courtauld Institute as part of a series of lectures presented under the banner of ‘Global Conceptualism’.

First I need to provide a bit of context. Anton Vidokle is an artist and founder of e-flux which is actually quite an ambiguous entity, an international mailing list, an artist-run organisation, a production company perhaps, even a small store-front in New York – above all an internationally recognised brand in the globalised/networked/transantional artworld.

In fact it is difficult to define because it is probably best described, as Anton does, as an artistic practice even though it tends to resemble many other structures from business organisation to social scenario. In any case, the potted history of e-flux begins in the late 90s when Anton and long-term collaborator Julietta Arranda sent out an email promoting a very low budget exhibition that lasted for one night in a hotel room in New York. That night hundreds of people visited the show and in turn it inspired Anton and Julietta to continue developing what became possible through email, which at the time was reasonably new technology. The email newsletter is now an institution in itself and e-flux boasts a dedicated audience of over 50,000 people. Thousands of museums and institutions the world over announce exhibitions, events and news items using e-flux and it has become an internationally recognised brand.

E-flux is now also a multi-million pound business and the income has become an unprecedented support system that has transformed e-flux into a complicated organisation which is not directly comparable to any other. Its hybridity as a compounded artistic practice adds an additional complexity. I want to focus on some specific terms Vidokle uses to describe his position as an artist and appropriate some of the terminology and methodology that he used in his lecture “Art without work” to further my own analysis. I will do this without responding directly to Vidokle’s specific thesis but by illustrating some labor practices to provide us with new tools to take a critical perspective on modes of distribution and possibilities within ‘globalised’ artistic practice. Subsequently I want to introduce ethical questions relating to freedom, sovereignty and the universalised ‘place’ of a transnational art market.

E-flux is run by artists and has operated many projects in its store front space in New York and more recently in a building in Berlin which operated as an experimental ‘exhibition as school’ for several years. The school, called Unitednationsplaza, was then ‘toured’ to Mexico City where I personally participated for the whole month duration with 19 others to loosely discuss the notion of ‘agency’ within artistic production. It is from this sense of proximity that I want to discuss this. It became clear to me at that time that through the association of this powerful exercise in branding I was able to access buildings, social scenarios, collections and people I would not ordinarily be able to. As long as I stuck with the crowd we would be taken to collector’s houses in huge modernist villas tucked away behind gates and armed guards in the hills surrounding Mexico City; to enormous warehouses just past the shanty towns to look at corporate collections of art in humidity and temperature controlled conditions. We would be carried in armoured cars to Thomas Hirschorn’s museum after-party and sit in the luxury living rooms of Mexico City’s wealthiest citizens. What is interesting here is that I was able to be invited into particular scenarios that I do not have access to in my home town of London.

In his lecture, Vidokle discussed the French Revolution as a pivotal moment in which artists were, for the first time, liberated from their subservience to and instrumentalisation by either the church or the aristocracy. The citizen artist was to have new working conditions, a tabula rasa on which to construct what it may mean to liberate artistic practice. However, he specifically used the term ‘sovereign’ to label the post-revolutionary

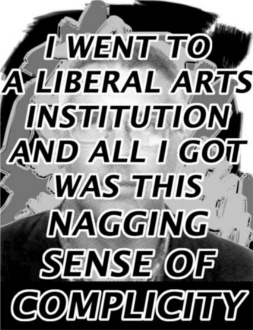

image by Huw Lemmey 2010

artist – the artist with a social agency. The discourse which has shaped my own practice and is characteristic of the artist’s whose work I most admire is the struggle for autonomy, criticality, a belief in artistic agency, self organisation and self-sustainability. In my opinion Anton Vidokle is a prime example of this yet the structural conditions which privilege his position are fascinating to the point that they illustrate a wholly original approach to fundamental terms relating to phrases such as ‘freedom’, ‘subjectivity’ and ‘empowerment’. I will argue that because of the technological and economic specificity of e-flux it is embedded entirely within the current paradigm of neo-liberal globalisation and therefore recontextualises these key terms to support the furthering of interests of capital.

His network is unparalleled in terms of profile yet he has no direct obligation to any particular institution, and perhaps, I might argue, no obligations towards nationalistic boundaries or citizen values, only individual artists, curators and other cultural operators who share the conditions of mobility and reasonable art-world status. The ‘sovereign’ artist, after all, works for no one. Vidokle travels effortlessly around the world touring the

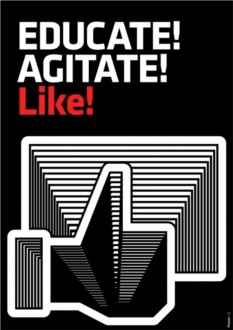

image by Deterritorial Support Group 2010

e-flux projects to state and city museums, galleries and project spaces across the globe. Additionally to this, in his lecture, Vidokle expressed his concern that artistic sovereignty or this utopian notion of a “post-revolutionary practice” was challenged again in our times by the global art market and the specific conditions that it dictated towards the products, concepts and services that it distributes. He continued that it was also under threat from the institutions that, with coded and conditioned support from private donors or state funds, instrumentalised artists to limit and shape the meaning of the works they would support.

I would agree that this is probably true but what would the ‘sovereign’ artist do to operate through and against this hegemony? Before I go into this, I want to make a clear delineation as I believe that the term ‘sovereign artist’ is misleading when coupled with a comparison to the ‘citizen’ or ‘post-revolutionary’ artist and paradoxically compared to Vidokle’s (and any other contemporary artist’s) self identification. Indeed, and e-flux is a perfect example, what we are discussing in fact is the ‘sovereign corporation’ or the ‘sovereign brand’. What allows individual sovereignty in this particular context is the rejection of subjectivity and the application of the corporate mask. One artist recently showed me – with some humor – two credit cards, both embossed with his name, one referring to him as an individual and the other to his company - same name, different legal identity.

For example, in the abstract for his lecture Vidokle asks “if the ultimate condition of production of art is life in the world, can art simply come about through a certain way of being with others?” If art is indeed indistinguishable from life, yet today’s artists are no longer physical beings, rather corporate or branded concepts, then this art would have to be just social networks in which works, projects and artists would all become symbol in itself, detached from individual subjectivities yet also somehow imbued with a sovereignty or agency that is paradoxically the supposed privilege of the subject or citizen.

This difficult idea is illustrated most acutely in The Martha Rosler Library, which is a ‘project’ produced by e-flux which features all of the books stored in the artist’s house formed into a library and exhibited like an exhibition. This illustrates the transition of artist to image and the ambiguity that is created in this paradoxical object imbued with the qualities of subjectivity. The need to constantly shift registers from the public to the personal, the local to the global and from the indivudual themselves to the representation of the individual is almost dizzying.

“Smart, decidedly political in orientation, often funny, and all over the place (in that way a perfect mirror of its owner), the library is packed with essential reading and titles that even your better bookstores would love to get their hands on. As the product of decades of avid reading, the contents of the library are both the source of Rosler's work and an installation/artwork that continues many of the concerns - with public space, access to information and engaged citizenship - that traverse her entire oeuvre.”

Elena Filipovic, If You Read Here… Martha Rosler’s Library, Afterall 15 2007.

In this quote, Filipovic discussed the various territories and representational associations that are brought together in The Martha Rosler Library, which toured extensively in western European institutions. The ambiguity here is the constant shift from personal register to iconic representation. We are encouraged to decipher whether the library represents Rosler herself, or the branding of Rosler within the late, museum era of her career. Is this an ironic gesture to criticize the reification of knowledge and arts possibility for direct exchange with its audience? Or is it just what is described on the e-flux website – a way around Rosler’s storage problems?

The other element of this project is its territorial movement. The ‘international tour’ is consistent throughout most of the projects facilitated by e-flux and through this mobility, e-flux creates a wholly unique production process. Indeed, it is the movement of this project ,already imbued with all these representational ambiguities, which actually serves to help us locate a less ambiguous, real geographical and political ‘place’ of the global economy.

Through its international mailing list, on which over 1000 art organisations around the world pay to advertise their exhibitions, e-flux raises funds to create projects and support a close network of artists and participants which it will also in turn promote on its mailing list. The exposure that the mailing list affords e-flux, the networks of the artists who are in part supported by it and the quality and specific nature of the projects which it hosts then leads to their projects being toured in the very institutions that hire advertising space on the mailing list. Effectively ‘selling back’ the projects which institutions indirectly fund is a unique and financially impressive yet provocative business model.

I believe that this is not too dissimilar to the relationship that is played out in the ongoing conflict between private and public spheres. I believe that there is a similarity between this and the relationship between multi-national corporations and the state especially in the post-crisis period of bail-outs, nationalisation and the playing-out of further liberalisation in terms of policy and regulation. Indeed, to cast e-flux as artistic service providers compliments the general theme of the projects, not explicitly generating wealth but providing a private/public approach to delivering projects to institutions. May I add also, that ‘private’ here is not so clearly delineated as, in the point identified earlier, most institutions and certainly all international biennials are instrumentalised, facilitated and partly supported through state funding.

image by Deterritorial Support Group 2010

Furthermore, it is absolutely reliant on the contemporary distribution of art which is subsumed within neo-liberal economics and power relationships. Indeed as email itself grew as a marketing tool making e-flux a viable business, the idea of notifying a ‘global’ audience about exhibitions can only exist within our contemporary technological and economic situation. The global markets in art have developed hand in hand with the neo-liberal project which in turn goes hand in hand with the massive redistribution of money away from the poor towards the rich. It is also contextualised by the re-casting of post-industrial nations as service providers. In this ‘globalised’ market it is important also to note the ‘place’ in which e-flux operates. Indeed it serves a vital purpose for museums and biennials across the world to make announcements, in English, to a centralised, predominantly western European and North American market place.

Within this context I would like to return to the idea of the ‘sovereign artist’ or ‘sovereign brand’ in relation to the free flow of capital and goods across national boundaries primarily in the interests of commerce and corporate gain. As the first multi-national corporations that, structurally speaking we would recognise today emerged in the late 19th Century, Ronen Palan, amongst others, has explained how sovereignty was itself commercialised.

“The improvements in communication and transportation technologies and accelerating capital mobility have been accompanied not by any loosening of the juridical unity of the state but by, if anything, the strengthening of it. The ensuing conflict between the increasing insulation of the state in law and the internationalization of capital forced a series of pragmatic solutions, one of which proved conducive to the development of the tax haven and the commercialization of sovereignty.” Ronen Palan (Tax Havens and the Commercialization of State Sovereignty)

In this situation we can identify an interesting paradox, the use of the principle of sovereignty against itself. Reinforcing the borders and juridical territory of the state only in order to transgress this border. To return to my previous point, individuals cannot cross this border but ‘sovereign individuals,’ those branded, fictionalized entities have total mobility on the condition that they can afford this ‘luxury’ of a very specific kind of freedom. Perhaps we can look to Bataille’s secret society Acephale to shed light on the freedom that is provided by withdrawal. Indeed, with the possibility to purchase sovereignty and the connection between this and the development of the tax haven, we have a new corporate class able to disappear vast sums of money in complex offshore arrangements; a veritable secret society in itself. What I am positing here is that it is possible to read the international operations of e-flux as somewhat a reenactment of these forms and thus not only re-framing notions of agency and ‘freedom’ within the contemporary liberalisation and de-regulation of capital flow but providing us with a ready-made tool kit in order to question the ethical impact of such practice.

As food for thought, in the context of my brief analysis I was left with a sense of unease as Anton listed his admiration for Rikrit Tiravanija’s ability to ‘withdraw’. The artists who is renowned for cooking meals apparently describes the process of cooking as allowing him the freedom to not be ‘present’ at the meal as the artist and allows him to avoid the undesired task of talking about his work. It might be over-dramatic but this method of production is undeniably exclusive and is of greater import when we consider responsibilities such as accountability, publicness and the relationship to the state. When considering what action can be taken by artists, seeking empowering self-organisation, perhaps exclusivity is now a key concern, perhaps we now have to compete for our “sovereignty” as the audience are recast as clients of our art-based’ services.