Steering clear of absolutist atheism

Both in my latest book and in my recent writing, I have been working around the possibility of a strategy of radical atheism. Developing the seminal work of the German philosopher Max Stirner[1], I defined radical atheism as a process of individual disentanglement from the web of injunctions and demands laid all around us by normative abstractions. I defined as ‘normative abstraction’ that particular position which abstract constructs typically occupy as soon as they cease to be docile tools in our hands and rear their head to the point of shaping, defining, and ultimately controlling our lives. Particularly, I focused on the most recent occupiers of this position, such as the burgeoning religions of work, gender, ethnicity, nationality, and so on.

My radically atheist attack against normative abstractions, however, was for the great part dissimilar from traditional atheism. While traditional atheism locates its critique on an ontological or epistemological level, deriding the belief in God on the grounds of its ‘falseness’ or non-demonstrability, my proposal for radical atheism disregarded such issues entirely. My project was – and it still is – concerned exclusively with ethics, that is, with the individual’s quest for the ‘good life’.

My unwillingness to subscribe to a traditional atheist critique of religion originates from an acknowledgement both of its inner limits, and of its ethical implications.

On the one hand, an attack on religious constructs based on their ontological and epistemological fallacies, falls victim of its own weapons. Any deployment of rational argumentations ultimately relies on a set of fundamental assumptions, which can be endlessly debunked in their arbitrariness, in an infinite drift towards an horizon of truth, ever-receding beyond our reach. As proved by the ancient Skeptics, rational argumentations can spin indefinitely in their spiral motion towards a theoretically unshakable foundation of truth. This particularly applies to the recent marriage of atheism and rationalism, with thinkers such as Dawkins and other science-fundamentalists as its main flag-bearers. Their reliance on the truth of scientific materialism only superficially differs from that religious naivete which they attribute to their adversaries, while often surpassing traditional religion in its noxious self-confidence.

On the other hand, I imagined what would happen if we really, honestly embarked on a systematic abandonment of all that isn’t rationally demonstrable. In one of those paradoxes which seem to recur throughout the ironic plot of history, such atheism would spin on itself to the point of perfectly resembling an extreme form of religious mysticism. If we decided to live by the merciless parameters of rational investigation, thus refusing any dealings with anything short of the demonstrable rational truth, we would soon find ourselves floating hopelessly in the infinite space of the undecidable, of the unspeakable, of the impossible. Similarly to the ancient mystics, we would be crushed under the weight of what lies beyond us, while somatising the pangs of its absence in the form of destructive hyperactivity or of spiritual catatonia, what Nietzsche used to define respectively as active and passive nihilism. The crusaders and Simeon the Stylite, the terrorists and the primitivists. The annihilation of life.

For these reasons, I did not found of my project of radical atheism within orthodox rationalism. I decided to ground it in ethics, within a path of autonomy and emancipation.

The individual self, enjoyment and autonomy

My first concern was to define the object of my atheism. While I wasn’t interested in building a court of the inquisition against falseness, I was indeed keen on disentangling myself from what was detrimental to me. I limited the function of my atheism to that of an antibody, whose first duty is to discern between what is useful and what is damaging to me, while avoiding the unbridled frenzy of an autoimmune disease. It might thus happen that radical atheism will accept to coexist with some normative abstractions – sometimes only for a for a specific length of time – because of their particular usefulness within a larger context. This is the case, for example, with the abstraction of language, which we employ to communicate with each other, but also, and most crucially, with the abstract construction of the individual self.

Since my perspective is that of individualist anarchism, the issue of the individual self is particularly important to my strategy of radical atheism. Nonetheless, I have no hesitation to admit the arbitrariness of its constitution. As it has been repeatedly demonstrated throughout the history of philosophy and of psychology, the concept of the individual self is vulnerable to a number of possible confutations. It is possible to argue that it is too large a concept, since it hides the infinite fragmentation of its composing parts, but it is equally possible to argue that its scope is too narrow, as it would be possible to melt its boundaries into much larger constructs, all the way to the all-encompassing Parmenidean ‘One’. Finally, it is also possible to argue convincingly that the individual self is just altogether incorrect as a definition, since it disregards countless fundamental forces which traverse it while remaining external to it.

Yet, I reclaim my choice of the individual self as the unit of measurement both of ethics, of radical atheism and of an existential anarchist project of emancipation. Despite it being an ‘essentially unreal’ entity, completely arbitrary in its construction, its deep connection with the flow of enjoyment reveals it to be a useful tool within a strategy of emancipation. As I will attempt to explain why this is so, I will try to condense into words a number of processes and functions which by their nature exceed language. I beg the reader to test my necessarily insufficient propositions not against the limits of language itself, but rather through a resonance with their own life. Although lacking the style and cadence of poetry, I will rely on the immediacy of poetic expression and intuition to unfold my argument. Similarly to music, the proof of my failure or success will be in the listener’s ear. Ultimately, as with many other fundamental matters, it should not be a matter of semiotics, but of aesthesis.

I mentioned the individual’s functional connection with enjoyment. Enjoyment is here a word – arbitrary, as all words – standing for that galaxy of feelings and perceptions which are commonly defined as pleasant, joyful, content, fulfilling, invigorating, thrilling etc. Whenever we experience such sensations, we have the impression that our enjoyment reaches us while remaining somehow external to us, like something that traverses us. If enjoyment flows through us, the individual self is the riverbed over which it passes. Only, the individual self is not just a mere riverbed. As well as supporting the flow of enjoyment, it has also the ability to regulate the speed and the intensity of its motion. It is capable of ‘tuning’ it, like the airflow though a brass instrument. This double function of supporting and tuning the flow of enjoyment, becomes particularly crucial if we consider the Cyrenaic[2] definition of pleasure as a smooth motion ‘which may be compared to a gentle rocking of the waves’.[3]

Indeed, the problem of regulating its motion lies at the heart of the malaise which often follows enjoyment, and which within late-capitalist societies takes dramatic proportions. As it is often noted, contemporary capitalism in no way resemble the inhibiting traditions of the past, which aimed at regulating the flow of enjoyment by significantly slowing it down, occasionally even attempting to dry out some of its most controversial streams. On the contrary, enjoyment is the fuel of today’s libidinal economy. Instead of slowing it down, however, contemporary capitalism typically accelerates its motion to paroxysm, ad infinitum. As Oswald Spengler precisely pointed out almost exactly a century ago[4], a tension towards infinity is the central dimension of Western society. In this late era of its existence, as its structures are increasingly sinking into the body of its members in biopolitical forms, infinity is forcefully injected as an uncontrollably rapid motion of enjoyment. Thus infinitely accelerated, enjoyment traverses human senses with the power of a water cannon, while smearing them with the mark of its passage as a sense of nausea, panic and ultimately, paralysis.

Yet, unlike the capitalist ideology of uncontrollable enjoyment, an individual can aspire to reclaim the possibility of regulating the motion of his/her own enjoyment, of tuning it in accordance to his/her own unique biology and psychology – like a string instrument is tuned according to the conditions of its woodwork. When the tuning resounds with the unique taste and ear of the individual, the ‘smooth motion’ mentioned by the Cyrenaic philosophers is achieved, and with it, pleasure.

From this definition of pleasure we can derive a notion of autonomy as the process of regulating the motion of one’s enjoyment according to one’s specific framework and taste. Consequently, we can define emancipation as nothing more than the condition which allows autonomy to take place. A struggle for emancipation is a struggle for autonomy, that is, a struggle for pleasure and self-determination. It is in reference to emancipation that the usefulness of atheism should be tested.

Social divinities, rebel dummies

While being ground on the individual self, emancipation has to take place within a social context. The singular individual often finds his/her autonomy challenged, not only by the technical difficulties of supporting and controlling the motion of enjoyment, but also by the pressure exerted on him/her by the social context.

If absolute atheism is simply unadvisable on an individual level, it seems to be downright impossible on the level of social organisation. Outside of the tight networks of friendship and loving relationships – and of few other fortunate circumstances – Max Stirner’s Unions of Egoists appear to be nowhere to be found, at least in their purest form. Although in my recent book I advocated the creation of communities which were not “built around a central totem”, simple observation seems to suggest even to me that this might not be possible outside of the territory of love and friendship.

In our common, social dealings with each other, a form of politeness imposes the invocation of normative abstractions as the guarantor of our relationships. In order to be able to deal with each other without fear of the other’s autonomy, or to reassure the other about the absence of our own, we present our words or actions as if they were produced ‘on behalf of’ or ‘in the name of’ a superior, impersonal entity. We deal with each other as men and women, as belonging to social classes, as citizens, or even simply as members of Humanity. Especially, we invoke Humanity to politely cover our empathy, perhaps one of the most startling marks of our individual autonomy. And whenever traditional abstractions begin to fade, we relentlessly invent new ones - typically defined as our ‘identities’ – to which we can assign the responsibility for our actions, words, feelings and behaviours.

Those which I previously defined as the central totems of social life perhaps would be better described as rebel dummies sitting on our shoulder, who are acting as our imaginary ventriloquists.

These rebel dummies, the invisible entities which I also defined as normative abstractions, assume and socialise the role that used to be of the Socratic daimon. Most conversations between humans are in fact conversations enacted on behalf of their abstract dummies, just like most fights are in fact battles between flags – although the blood that is spilt during them is always all too human.

The position thus occupied by a normative abstraction is one of power par excellence. Sitting on a person’s shoulder, making him/her act and talk on its behalf, the normative abstraction remains perfectly inactive and silent: their subjects act and talk on their behalf. This is perhaps why the God of monotheistic religions has long ceased creating and speaking. An all powerful God can’t be anything else but mute and immobile: any word, any action, would reveal not only its incompleteness, but also its obedience to a higher voice and a higher will.

The only activity which normative abstractions and divinities alike allow themselves – apart from franchising their name as a justification for human actions – is the consumption of the sacrificial offerings which are presented to them. Divinities might be immaterial, but they still require feeding in order to continue existing. Although it might prove impossible to completely abandon social divinities within the social context, a degree of discretionally is still available to the individual in preparing this banquet. It is here, while feeding those divine rebel dummies, that the individual might still find a way to safeguard his/her autonomy – not through acts of heroism, but through the skilful use of a form of cunning strength which the Greek called metis[5].

Divinities live off their subjects’ submission. As they are unable to operate – paralysed as they are in the position of power – the obedience which they inspire constitutes their only diet. Submission can be presented to the devouring divinities in two different forms: either as submissive behaviours, or as performative representations of submission. If submissive behaviours constitute the food of the gods in its purest form, performative representations of submission are its spectacular, yet empty surrogate. Here the story of Prometheus comes to mind, when he presented to Zeus two piles of sacrificial offerings, one composed of good meat, the other of bones wrapped in fat. Zeus fell for the trick and chose the latter. A similar act of cunning metis is still possible today, each time a person is forced – or strategically decides – to rely on the use of normative abstractions.

Catholicism as radical atheism

Perhaps these two different ways of feeding divinities can be best explained metaphorically, by comparing the inner functioning of Catholicism as opposed to that of Protestant Christianity.

When Protestantism emerged, first with Luther and subsequently with a plethora of other reformers, the main object of its attack was the progressive desacralisation of religion which was brought about by Catholic corruption. Indeed, this accusation couldn’t have been more poignant. Already over a millennium old, the Catholic Church had long turned into a flamboyantly ritualistic, political and social institution, thinly disguised as a spiritual authority. The secularism of the Catholic Church wasn’t confined to the corrupted ecclesiastic hierarchies, but had its roots in the lifestyle of the millions of devotees which constituted its rank and file. Originally tainted by rural superstition and Roman paganism, everyday Catholicism had progressively developed – particularly in Southern Europe – a pronounced tendency towards radical atheism.

Through its extensive use of spectacular rituals, and more generally through an iconophilia which contrasted with Protestant iconoclasm, Catholicism had turned into an inexhaustible divine kitchen, offering God the most luscious replicas of authentic spiritual food. While Protestants advocated true, honest, humble submissive behaviour to God, Catholics constructed elaborate, ritualistic representations of submission. Protestants ached for deeper, more authentic ways to truly repent for their sins and enact God’s commands, while Catholics sublimated guilt and obedience in extraordinary displays of their representational equivalents. Protestants could torment their own flesh and soul through their entire life, begging forgiveness and moulding their soul to be a perfect instrument in God’s hands. Catholics, in the most extreme scenario, would physically flagellate themselves for a few minutes during a public procession, and then would consider their debt to the divinity to be fully paid.

At the heart of Catholic practice – that which Mario Perniola defined as the ‘Catholic feeling’[6] – lies the unsettling realisation that its core functioning is that of an exorcism: not an exorcism of the Devil, but of God. The complex net of rituals woven throughout the centuries by Catholic priests and believers functions as a trap, laid down to catch the passage of God with his retinue of feelings of guilt, voluntary servitude, religious morality, and so on. By entangling normative abstractions in rituals, Catholics manage to limit their influence, circumscribe their existence, and ultimately free themselves from the duty of feeding them with the real flesh and blood of their daily behaviours. Outside the ritual, there lies autonomy – as outside language lies the object of its utterance.

Conversely, the Protestant refusal of ‘unreligious’ Catholic rituals and habits broke this magic cage, thus freeing God and its ravenous entourage. In Protestant culture, the divinity – God as well as its contemporary social equivalents – has to be fed not with representations of repentance, but with true submission, not with limited performances of sacrifice, but with actual, continuous, painful martyrdom. To say it according to contemporary managerial parlance, one doesn’t simply have to work: one has to truly ‘love’ his/her job. Here lies the reason behind Calvin’s attack on Catholic ‘Nicodemism’[7], or Della Rovere’s ‘Exhortation to Martydom’[8]. If the excessively adorned Catholic church is a dungeon where the spirits of religion languish, as they are restrained from affecting actual human autonomy, the unadorned Protestant hall is a trap for humans. Within the bleached white walls of the Protestant mind, a person is left alone under the heel of God’s injunctions.

On the basis of what has been discussed so far, it might not sound too surprising to claim that the Catholic approach is, perhaps, the only possible method of radical atheism. By calling ourselves ‘individual selves’, and by performing as such, we might be freed from the spectre of individuality and of the self. By performing social functions with the dexterity and cynicism of a consumed actor – that is, by strategically employing some characters commonly associated with psychopathy – we might be freed from the risk of truly embodying them in our innermost depths. The modesty which a person shows with regards to what is most dear and intimate to him/her, for fear of losing it, should be an indicator of the possibility of employing representational public display as a tool to exorcise and restrain that which is most dangerous to us.

Conclusions

I began this essay mentioning my recent work on radical atheism. Through these pages I attempted to develop my strategy of radical atheism in the light of a pessimistic – or perhaps realistic – understanding of the seeming inescapability of some normative abstractions. While for some of them, such as the individual self, I claimed a particular existential usefulness – in the interest of autonomy and emancipation – for others, such as social normative abstractions, I conceded that within the broad social world as I know it, they simply seem to be unavoidable. Although I despaired of the possibility of doing without them outside of relationships of love and friendship, I did not rule this out entirely, nor did I deny the ideal desirability of their removal – as I also discussed at length in my latest book. In the light of these considerations, I attempted to draw a practical strategy which, while falling short of absolute atheism, would allow the individual to maintain a radically atheist approach.

I tailored this strategy for those situations in which an individual might be stuck in a position of powerlessness against normative abstractions, or might be forced to accept them at least to a certain extent. The aim of this essay has been to think about how an individual in that position might concede as little as possible to the cult of normative abstractions, while effectively safeguarding his/her own autonomy.

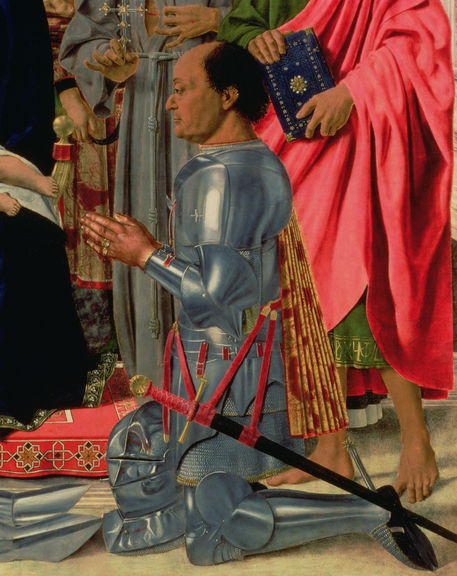

To this end, I advocated the usefulness of a – metaphorically – Catholic approach. I characterised Catholicism as a net of empty representations, which can be employed to entrap a normative abstraction – in this specific case, God and religious morality – while nominally keeping it alive. This allows us to do without both the dangers of absolute nihilism, and those of actual religious submission. This representational pretence of belief can be compared to the ‘simulation of competition’ enacted by Condottieri and mercenary troops in Renaissance Italy[9], and is squarely opposed to the Protestant approach. I outlined the core Protestant attitude as devotion to transparent honesty rather than to Baroque artifice[10]; as a desire for repentance and suffering which is so deep to the point of being invisible, rather than the flamboyant representation of pain that characterises Catholic statues of martyrs and saints. In a word, I chastised Protestantism for its naivete in the face of the terrifying power of normative abstractions, and I advocated a Catholic strategy of cunning as an effective form of radical atheism.

While in my book I discussed the all-out atheism of the adventurer, in these pages I focused on the less heroic – yet perhaps more frequent – guerrilla warfare of a radical atheist stuck in contemporary society. Although I only focused on the theoretical structures of this type of (anti)spiritual warfare, I encourage the reader to test their relevance in the face of daily challenges such as employment/unemployment, citizenship, gender normativity, political allegiances, and so on. I look forward to writing more about this in a future series of essays.

[1]Max Stirner, The Ego and His Own, Verso, 2014

[2]The Cyrenaic school of philosophy was founded by Aristippus the Elder and flourished in the Hellenistic era. It proposed a form of ultra-hedonist ethics, complemented by a unique ontology of becoming. There is still little academic material available on them, but Ugo Ziolioli’s book The Cyrenaics (Aucmen, 2012) is an excellent and penetrating introduction to their thinking, and particularly to their ontology. I also wrote an outline of Cyrenaic philosophy in relation to existential anarchism, online here.

[3]Aristocles, cited in Eusebius, Preparation for the Gospel, 14.18, 764ab; G IVB 5

[4]Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, Cambridge University Press, 2003

[5]An interesting analysis of metis can be found in Lawrence Freedman, Strategy, Oxford Univesity Press, 2013. I also discussed it at length in my essay The Cunning Man, for E.R.O.S. Journal, Issue 4, 2014

[6]Mario Perniola, Del Sentire Cattolico, Il Mulino, 2001

[7]Nicodemus the Pharisee is mentioned in the Gospel of John 3:1-2. While outwardly remaining a pious Jew, he used to visit Jesus secretly by night to receive instruction. Jean Calvin introduced the word ‘nicodemism’ in 1544 in his Excuse a messieurs le Nicodemites.

[8]Giulio della Rovere (1504-1581) was an Italian Augustinian friar who converted to Protestantism. He authored an Exhortation to Martyrdom in 1552.

[9]During the Renaissance, large mercenary armies were employed by the many warring Italian states. Often under the leadership of a Condottiere, mercenaries were infamous for fighting each other in bloodless, almost mock battles. A good account on this phenomenon can be found in Geoffrey Trease, The Condottieri, Thames and Hudson, 1970.

[10]For a further discussion of the relationship between Baroque artifice and anarchist emancipation, please see my forthcoming article‘We Have Nothing of Our Own But Time’: Baltasar Gracian’s strategy of disrespectful opportunism.